FITCHBURG -- George Mirijanian arrives an hour early and finds the switch beside the door in Room C159 of the McKay Campus School.

Narrow tables placed in rows, 30 swivel chairs around those, a coat rack, and a school clock five minutes fast flicker into view. The room has neither windows nor decoration.

Mirijanian, a former president of the Massachusetts Chess Association and program director of the Wachusett Chess Club, is a writer, educator, and chess expert.

"A friend of mine from high school taught me how to play when I was 15," he says in his radio announcer's voice, gently tugging the beard that brushes his plaid collar. "That was 1958. I caught the bug. It's a passion -- an addiction."

In his 1750 treatise, The Morals of Chess, Benjamin Franklin warned that the hobby easily becomes an obsession. Many enthusiasts have gone mad in pursuit of the perfect game. Harry Nelson Pillsbury, a Somerville native and contender for the World Championship, had a nervous breakdown following an exhibition of blindfolded play and attempted to throw himself from a hospital window. Former world champion Wilhelm Steinitz spent months in an asylum for the insane after losing his title. On Chess Chat, the monthly Fitchburg Access Television show he hosts, Mirijanian once described a good player who managed to quit: "He gave up chess cold turkey. ... He was engaged to a woman who said, 'It's me or the game.' It takes a very strong person to do that."

Andrew Paul of Leominster arrives shortly after George and me. At 25, he is one of the club's youngest members and joined recently.

"Why don't you two play a fun game before the tournament begins? A 'fun game' is what we call a game that's not officially counted," George Mirijanian explains. "Really, they're all fun."

"What's your rating?" Andrew asks, setting up a board. I do not have one and think he will clobber me because he does. George explains that everyone in the club has a rating, a calculus of cumulative wins and losses. If you win a game, you gain points -- a lot of them, maybe 30 if you prevail against someone with a high rating. Lose a match, lose points, particularly if you play against someone with a low rating.

Andrew Paul: 997. George Mirijanian: 2009. Bobby Fischer, considered one of the greatest players of all time: 2,785. Members of the Wachusett Chess Club are "point proud" and like comparing ratings and seeing theirs go up -- a testament to how many games they have played and how skillfully they played them.

"I'll play white," I tell Andrew. White gets to go first. Most players regard this as an advantage. We both open with the same move -- scooting the pawn out in front of the king, more-or-less protecting the center of the board and creating an opening for the bishop and the queen.

I move my knight from its starting position and threaten Andrew's pawn. He moves another pawn to protect it. This is one of the most common opening sequences -- not particularly interesting to the seasoned player, but safe and reliable. Andrew makes a mistake. I sneak my queen through his defensive line and take a rook. Two dozen moves later, I checkmate Andrew's king and accuse him of going easy on me. He shrugs.

During our game, a dozen sturdy, middle-aged men wearing a comfortable-looking assortment of plaid, flannel, denim and corduroy entered Room C159 in ones and twos. Except for one man who has brought a polished wood case and another who has plastered his with photographs, the rest carry black bags with boards, pieces, and timers. Two men have mustaches, five are baldheaded, three sport hats, possibly to conceal baldness, eight have beards, and almost all wear a 36-by-29 pant. As they sit down and begin chatting, it seems as if chess is the only thing on their minds.

"Did I ever tell you that I competed for the Special Forces in '81 and '82?" says Gary Brassard (1815), a man with a thick neck, his upper lip bristling with gray hair. "When I played against the Army, I got killed."

On the other side of he room, Constantin Leonda (1367), a Romanian immigrant, holds forth on the subject of Bobby Fischer, who once played at the Wachusett Chess Club in 1964. "People say Fischer vas arrogant. He was number one. He has the right to be arrogant, I say. You can be arrogant, too, if you're number three, four, five."

For a moment, the low murmur of conversation ceases as George Miller (1525), an energetic, mustached man with the paunch of age, hauls a cooler through the door and onto the nearest the table.

"I vas feeling a bit thirsty," Constantin says.

"It's not what you think." Miller lifts the lid, revealing rows of iced chocolate and vanilla cupcakes. "For my birthday," he says

"How old might you be?" George Mirijanian asks.

"Seventy-one."

"Two years older than me. I believe that makes you our oldest member."

"You can have a cupcake if you'd like," George Miller tells me. I think he says, "Take as many as you want" and eat six. Miller is a retired professor of education from Ashburnham who believes chess is an effective cure for attention deficit disorder. "First, I play against a kid to teach him the moves. Then I let them play together. I stand at a distance and offer a little guidance. Then, they're usually good to go on their own," he says. Gail, the only woman present, buries herself in a pulp novel.

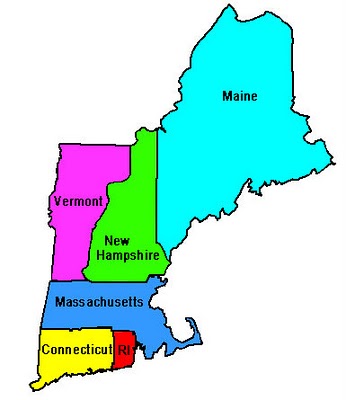

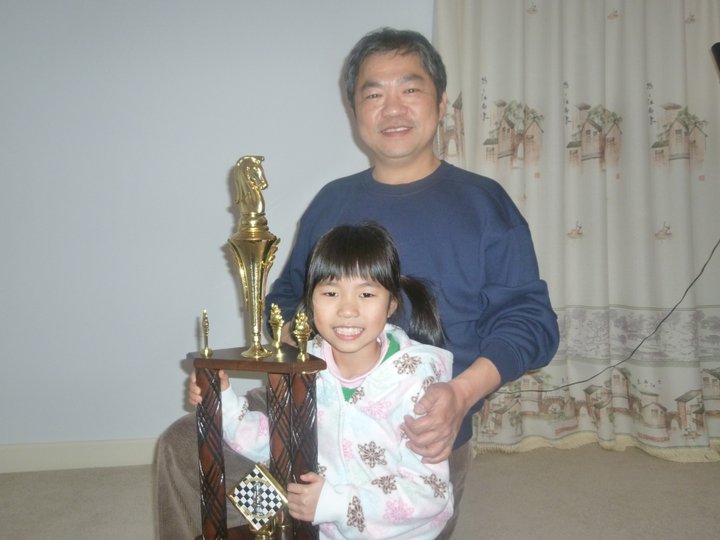

Percy Yip (1556) and his daughter, Carissa (1798), arrive in the nick of time. They came from Chelmsford. "Carissa Yip is the highest rated 9 year-old girl in the country," George Mirijanian brags. He likes to see young people "catch the chess bug" as he did in high school.

After one tournament, Mirijanian asks Percy Yip about his daughter. "Is she good at math?"

"She learns the material quickly," says Percy.

"Does she play an instrument?"

"Classical piano Monday night," Percy says. "She probably does not like to practice. She likes chess more."

"Music, chess, mathematics -- some kids are so bright they understand those things," Mirijanian says

Tonight's tournament was supposed to start at 7.

"Finally, we're all here," George says about 10 minutes later. The men, Gail and Carissa find their opponents. Carissa Yip, her frilly pink socks and pink shoes dangling 6 inches from the floor, sits across from Alan Condon (1549), a veritable bear of a man who wears earth-colored clothes, sandals, and a shaved head.

They begin to play, and the room grows silent except for the tick of chess timers, the thud of a pawn or knight against the board, the creak of chairs, and scratch of pencils as the competitors transcribe every move made. Silence during competition is a rule, but players would probably refrain from talking even if it were not. To play chess means abandoning spoken language. Chess is a form of communication. One player interjects a piece. The other responds, becomes defensive. A player makes threats with a limited vocabulary: pawns, rooks, knights, bishops, a king and queen.

Players mimic one-another, attempt to predict one-another's actions, and try to surprise an opponent with a daring move. They are like politicians locked in debate, each attempting to maximize the impact of his turn. Sometimes I think of a chess move as a comedic one-liner -- the unexpected is usually most effective.

"It's like music -- a universal language," George Mirijanian tells me. "I can sit down across a board from someone from anywhere in the world and play a game. They could speak Hindi, which I don't speak, and we could enjoy one another's company for an entire day."

One does not need to know how to play the guitar to appreciate the Beatles. However, an untrained spectator may have difficulty enjoying a game of chess. I wander from table to table trying to make sense of the games in progress -- and couldn't. One cannot learn as much from watching as by playing.

If asked for advice, most decent players would say the same things: protect the center of the board early in the game using any combination of pawns, knights, or bishops; don't bother moving the pawns in front of a rook to get the rook into play; place a knight in such a way that it can attack two or three pieces at once; don't overextend your pieces; if you have an advantage over your opponent, trade queens; avoid moving the same piece multiple times in succession; every move ought to have a purpose.

But how does one determine when a move has purpose? Or if a piece has ended up in a precarious position? Or if one player has a meaningful advantage? According to members of the Wachusett Chess Club the best way to learn is through practice and by replicating the games of slightly better players.

Andrew Paul quickly loses his game to Dave Couture (1651), a very strong player. They carry their board to a nearby classroom. Andrew carries a green, leather-bound book in which he records all of his games.

"I think you messed up when you moved your knight to the right side of the board," Dave says.

"I think so," agrees Andrew in an urgent whisper. He looks in his book and sets up the board to how it looked on his 20th move.

"That move doesn't look like it does anything," Dave says. "It just allows me to play over here. So we can't let me take that, we have to do something else besides letting me take there. That's all. Bring it back." They try the knight in a few different positions. A few minutes later, Constantin and Percy Yip join them and stand over the board.

"Vhat about the pawn? Make an exchange!" Constantin exclaims, grabbing a piece.

"You'll have to move something else," Percy says.

"All right. The rook isn't hanging, that's a plus," Dave says. "How about we do this here. We just give up the bishop." As the experienced players crowd around the board, Andrew nervously shakes his foot and fiddles with the flashlight attached to his key ring.

"You give up the bishop?"

"I give the bishop!" Dave says, swapping around a few pieces. "Then I can check with the rook." They rearrange pieces until Andrew wins the game.

Scott Bremer is a student at Hampshire College and a student in Yankee Magazine Editor Mel Allen's magazine writing course at the University of Massachustts Amherst.